Throughout our lives, all cells in our bodies experience a normal life cycle of growth, maturity, and death. During this time, our cells normally experience damage to DNA by normal functions of the metabolism, or exposure to certain environmental factors like UV light. Ordinarily, our body is able to repair the damage done to the DNA in order to restore healthy cell function.

The older we get, the more DNA damage we experience, and if damaged DNA is unable to be repaired, the cells become more susceptible to continued, erratic cell division, which often results in cancer. The cells of the body undergo a general wearing out process known as cell senescence, in which the cell ceases to replicate and is programmed for death. Senescence is a healthy, highly regulated process, and is crucial in the protection against tumor-growth.

It was previously considered by scientists that cancer development arises from rogue damaged cells that escape the natural cell death process and continue on to divide and grow. But scientists from the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center have discovered that epigenetics could play a large role in how normal cells can develop into tumor-promoting cells.

In the study published in Cancer Cell, lead author Dr. Hariharan Easwaran and his research team dove into to the epigenetic modifications occurring during cellular senescence that could result in cancer development.

“Senescence is a very well-known, normal aging process that is actually an antitumor mechanism. It occurs when cells perceive an excess of DNA damage, when cells undergo too many cell divisions or when they experience cancer development-related stress. So it was puzzling to us how the senescence process could lead to the formation of tumors,” said Dr. Easwaran.

They focused their attention on DNA methylation patterns in the fibroblasts of human foreskin samples how it can disrupt normal cellular senescence, allowing the progression of tumor growth. DNA methylation is the epigenetic process that silences gene expression by adding methyl groups to the DNA sequence, making it an appropriate target for studying the healthy function of the cellular death process.

In the experiment, these cells endured the laboratory process known as Weinberg’s classical transformation system, which converts normal, healthy cells to cancer cells by introducing genes that are known to promote tumor development. These newly transformed cells were then injected into mice so the research team could observe tumor progression. The researchers also allowed a second group of healthy fibroblast cells to mature into natural cellular senescence, and observed the DNA methylation patterns in both groups over time.

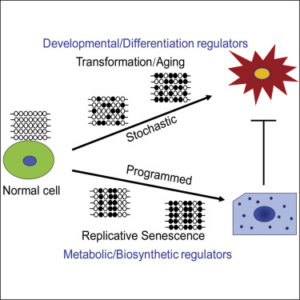

They discovered that the DNA methylation pattern in both senescent cells and transformed cells were initially similar, but the genes that were methylated along with the evolution of the cells were much different. Particularly, they found that DNA methylation in senescent cells was highly programmed, and had uniform epigenetic patterns among the different senescent groups. In transformed cells, they found that methylation patterns were highly erratic and random, and involved genes known to promote tumorigenesis.

In further experiments conducted by lead author Dr. Wenbing Xie, he found that he could not manipulate senescent cells into becoming cancer cells, confirming the protective nature that these cells have against tumor formation. In doing this, he also discovered a set of genes that are most vulnerable to cancer causing methylation, highlighting an important genomic region for future research.

The findings in this study suggest that hypermethylation to DNA promotor regions early on in cell development can hijack the senescence process and allow cancer cells to continually renew and multiply.

Dr. Stephen Baylin, one of the study’s coauthors believes their discovery is significant because it reveals the areas available to be treated to hopefully prevent future cancer development in aging cells: “Aging is probably the leading risk factor for most common cancers. Maybe you won’t find the Ponce de León Fountain of Youth, but if you could dampen down the risk of cancer for every decade you age, that could be huge.”

The scientists in this study hope that future research will focus on tissue-specific DNA methylation patterns in senescent and transformed cells in efforts to determine an individual’s risk for developing cancer as they age.

Source: Wenbing Xie (2018) DNA Methylation Patterns Separate Senescence from Transformation Potential and Indicate Cancer Risk. Cancer Cell, 33 (2).

Reference: Johns Hopkins Medicine. “Cancer Risk Associated With Key Epigenetic Changes Occurring Through Normal Aging Process” Johns Hopkins Medicine News & Publications. 22 February 2018. Web.